Niger J Paed 2016; 43 (1): 34-39

ORIGINAL

Musa S

Prevalence of hepatitis C Antibody

Yakubu AM

in Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Muktar HM

infected children

DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v43i1.7

Accepted: 25th October 2015

Abstract :

Background: Hepatitis

both subjects (92.3%) and controls

C

virus (HCV) is a major public

(100.0%). Injection at patent medi-

Musa S

(

)

health problem for Human Immu-

cine vendor (PMV) was noted to

Yakubu AM

nodeficiency virus (HIV) infected

be

the most risky practice leading

Department of Paediatrics,

population. Both infections share

to

HCV in children, with more

Muktar HM

same routes of transmission, and

than thrice the chances of HCV

Department of Haematology,

quite often co-exist, with dual

sero-positivity than in those who

Ahmadu Bello University Teaching

infections associated with recipro-

didn’t receive injections at PMV.

Hospital, Zaria, Nigeria.

cal and mutually more rapid pro-

Four mothers of the HIV-infected

Email: musa4all@gmail.com

gression than either infection

children were co-infected with

alone. Co-infection also adversely

HCV and none in the control

impacts on the course and man-

group. All 4 children of these

agement of both infections. This

dually infected mothers were also

study was carried out to document

co-infected. Controlling for other

the prevalence and determinants

factors, children of HIV infected

of

HCV sero-positivity in HIV-

mothers were more than twice as

infected children.

likely to have HCV antibody as

Methodology: A

total of

132 HIV-

children whose mothers were HIV

infected children attending the

negative (RR = 2.67). Similarly,

Paediatric Antiretroviral Clinic

HCV infected mothers have 12%

were recruited as subjects. An-

greater chance of transmitting

other 132 HIV negative children

HCV to their children than non-

matched for age and sex were

infected mothers and children de-

recruited as controls. Relevant

livered vaginally were 1.6 times

demographic data was taken from

more likely to have HCV antibody

each child. Blood samples were

than

those delivered via caesarean

also

obtained from each child and

section.

from their mothers when avail-

Conclusions: The

prevalence of

able, and assayed for the presence

anti-HCV in HIV-infected children

of

anti-HCV using a membrane-

is

significantly higher than that of

based immune-assay kit.

HIV uninfected peers. Factors

Results: The

sero-prevalence of

strongly associated with HCV sero

HCV antibodies was 9.8% among

-positivity identified are maternal

HIV-infected children and 3.0%

HIV and HCV infections, vaginal

among the controls. This was a

delivery and injections at patent

statistically significant difference

medicine vendor.

(p

= 0.042, Fisher exact). HCV

sero-postivity was more frequent

Key words: HCV;

HIV; children

in

children after 5 years of age in

Introduction

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

2-3 HCV infection acts

as

an opportunistic disease in HIV-infected persons be-

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and Human Immunodeficiency

cause of the increased incidence and accelerated natural

history in co-infected persons. HCV infection may also

4

virus (HIV) co-infection is a growing public health con-

cern. It has gained importance with decreasing AIDS-

1

impact the course and management of HIV disease, par-

related morbidity and mortality due to HIV treatment.

ticularly by increasing the risk of antiretroviral drug-

induced hepatotoxicity.

5-6

HCV/HIV co-infection is associated with higher HCV

viral load and a more rapid progression of HCV-related

It

is estimated that four to five million persons are co-

infected with HIV and HCV worldwide. According to

7

liver disease, leading to an increased risk of cirrhosisand

35

the World Health Organization (WHO), sub-Saharan

primary paediatrician managing the case.

Africa has the highest prevalence of both infections,

8

Approval of the Scientific and Ethical committee was

being home to almost two thirds (63%) of all persons

obtained before the commencement of the study.

infected with HIV and the majority of the 2.3 milion

children living with HIV worldwide and having esti-

9

Data Collection

mated 5.3% average prevalence for HCV.

10

Nigeria, with an overall HIV prevalence of 4.4%

11

in

Relevant data from all children enrolled for the study

2006and also appears to have a high incidence of HCV

was obtained and a detailed physical examination was

infection with estimated prevalence rates of up to 14%.

12

conducted at recruitment. Data obtained from history,

suggests a very high burden of co-infection with both

physical examination and laboratory results was re-

viruses and makes the country a potential source of an

corded into a specifically designed proforma.

emerging epidemic of HIV/HCV co-infection.

13

Prevalence rates of HIV/HCV co-infection depend on

Laboratory Methods

the mode of acquisation of both infections and the popu-

lation studied. Although both HIV and HCV share

Five millimetres of venous blood was taken each from

similar modes of transmission, the relative efficiency of

all patients and their mothers and centrifuged by the

transmission of the two viruses by different routes var-

investigator. Sera obtained were assayed for the pres-

ies. and mother to child transmission is the main route

14

ence of antibodies to hepatitis C virus (Anti-HCV). De-

of

acquiring both infections among children under the

tection of Anti-HCV was carried out using the HCV

age of 15 years.

15

One Step test kit for the qualitative detection of

antibodies to hepatitis C virus in serum or plasma.It is a

Only a few studies focussed on HIV/HCV coinfection

membrane-based immunoassay that is commercially

among the paediatric population even in most parts of

available.The kit has a relative sensitivity of 96.8% and

Africa and Nigeria where the potential for high disease-

specificity of 98.9%. Manufacturer's instructions were

burden exists.

16-19

Whether or not prevalence rates and

strictly followed to determine the serum samples that

other observations about hepatitis C virus and HIV co-

would be seropositive for HCV antibody.

infection in several adult populations can be projected to

children remains to be seen. This study therefore is

Data Analysis

aimed at determining the seroprevalence of HCV/HIV

co-infection in children aged 2 years to 15 years.

Data obtained from the study was analyzed using the

computer SPSS version 15.0.0. Results are presented in

figures, tables and graphs as appropriate. Differences

between proportions were evaluated by the Chi-square

Subjects and methods

test

with Yate’s correction applied as appropriate or

Study area

Fishers exact test was used where appropriate. A p-value

of

less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically sig-

The

study was conducted at the Paediatric Antiretroviral

nificant in comparative analyses. Relative risks with

(PARV) Clinic. The clinic is situated in a tertiary

95% confidence intervals were calculated.

referral hospital, and sees an average of 50 patients a

week from across the northern states.

Case Management of children

Study population and design

All children recruited for the study were routinely addi-

tionally investigated as appropriate based on their other

A

hospital-based prospective cross-sectional descriptive

presenting symptoms and signs to establish the existence

study of children between the ages of two years and fif-

or

otherwise of concomitant disease according to the

teen years attending the clinic was carried out. HIV

standard of care in the hospital. All the children re-

negative children, matched for age and sex, attending

cruited for the study were then managed accordingly

other paediatric specialist clinics, were recruited as con-

either in the Paediatric ARV Clinic, or the Paediatric

trols. Children were included in the study as cases if

Gastro-enterology, Hepatology and Nutrition clinic or in

aged between 2 and 15 years, have a HIV positivity and

any of the other paediatric units as appropriate.

are attending the PARV clinic. Inclusion in the study as

control was if they were aged between 2 and 15 years

and are HIV negative. Children were excluded from the

study if parents or caregivers declined consent for the

Results

study.

A

total of one hundred and thirty two HIV infected chil-

Ethical Consideration

dren who fulfilled the criteria for inclusion were pro-

spectively studied for presence of HCV antibody be-

Informed consent of each of the children’s parents or

tween November 2008 and August 2010 as study sub-

caregivers was obtained before recruitment into the

jects. Another 132 HIV negative children matched for

study. Pre-test and post-test counselling was done as

age and sex were studied as controls during the same

appropriate and test results were communicated to the

period.

36

Prevalence of antibody to HCV in study group and

Risk factors for anti-HCV positivity:

Controls

Table 3 shows risk factors of mode of delivery, early

Out of the 132 study subjects, 13 tested positive to HCV

breastfeeding status, and maternal anti-HCV, HIV status

antibody. This gives the prevalence of antibody to HCV

of

children with a positive anti-HCV in both study sub-

of

9.8% among the study subjects. Among the 132 con-

jects and the controls. Of the 13 study subjects with a

trols tested, 4 had antibody to HCV, giving a prevalence

positive anti-HCV, 12 (92.3%) were delivered vaginally

of

3.0% as shown in Table 1. The difference between

while 3 (75.0%) of the 4 controls with positive anti-

the two groups was statistically significant (p = 0.0142,

HCV were delivered vaginally. The relative risk of a

Fisher’s Exact test).

positive anti-HCV by vaginal delivery was 1.60 (95%

CI= 0.76 – 31.57) which was not statistically significant.

Table 1: Prevalence

of HCV

antibody in

study subjects

and

Eleven children with positive anti-HCV among the

controls

study subjects (84.6%) had been breastfed while among

Anti-

HIV

Controls

p-value

the controls, 1 (25.0%) of those with positive anti-HCV

HCV

(Fisher’s exact test)

had been breastfed as shown in table 3. The relative risk

Positive

13

(9.8)

4

(3.0)

was 1.18 (95% CI = 0.73- 6.10), which was also was not

Negative

119

(90.2)

128

(97.0)

0.042

a

statistically significant difference.

Total

132

(100.0)

132

(100.0)

Table 3 also shows HIV and HCV status of mothers of

Age prevalence

children with a positive anti-HCV among both study

subjects and controls. Not all mothers in both groups

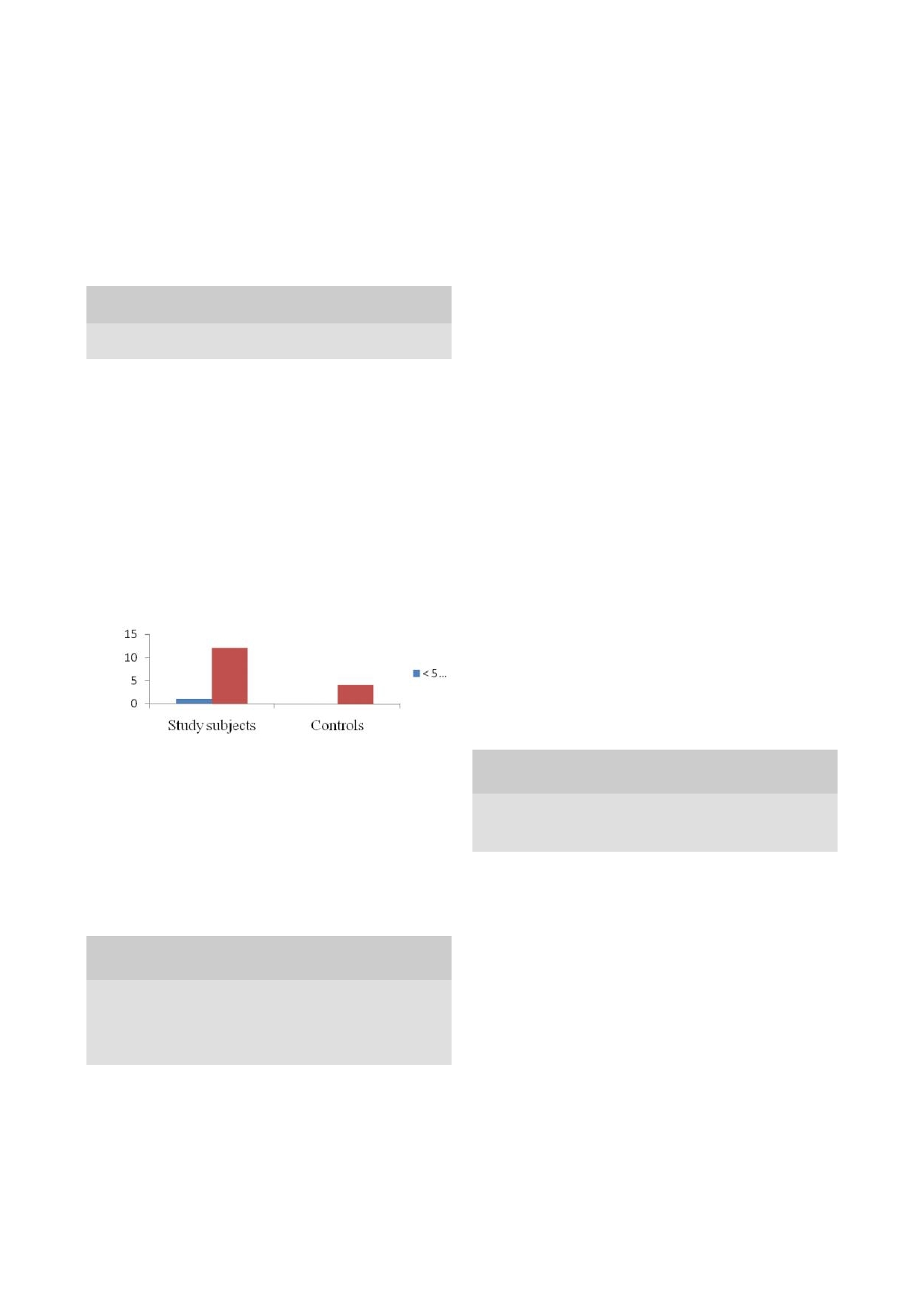

Fig 1 shows the prevalence of antibody to HCV by age

were available for testing. Four (44.4%) of the nine

among both the study subjects and the controls. Anti-

mothers of children in the study group also tested posi-

HCV positivity was detected more in children aged

tive for anti-HCV as against a mother (33.3%) out of 3

above five years in both study subjects and controls.

in

the control group. The relative risk for a positive anti-

This difference was statistically significant.

HCV was 1.12 (95% CI = 0.52 – 1.71). This however

(

χ2 = 1.000 with Yates correction, p = 0.00).

was not a statistically significant increased risk.

Similarly, 8(88.9%) of 9 mothers of children in the

Fig 1: Prevalence

of positive

anti- HCV

by age

among both

study subjects with positive anti-HCV were also HIV

the

study subjects and the controls

infected as against a mother out of the 3 (33.3) in the

control group. The relative risk was = 2.67 (95% CI =

0.83 – 33.18), which again was not statistically signifi-

cant.

Four mothers of the HIV-infected children were co

-infected with HCV and none in the control group. All 4

children of these dually infected mothers were also co-

infected.

Sex prevalence

Table 3: Maternally-associated risk

factors in

children with

positive anti-HCV among study subjects and controls

The distribution of antibody to HCV by gender is shown

Anti-HCV positive

in

table 2. Eight (6.1%) of the children among the study

Maternally-

Study

Controls,

Rela

95%

confidence

subjects who had positive antibody to HCV were males

associated

subjects,

n =

4

tive

interval

as

against 3(2.3%) among the controls. Five (3.8%)

risk

factors

n =

13

risk

among the study subjects with positive anti-HCV were

Mode of delivery:

females as against 1 (0.8%) among the controls. This

Vaginal

12

(92.3)

3

(75.0)

1.60

0.76 – 31.57

Caesarean

1

(7.7)

1(25.0)

0.63

0.03 – 1.32

difference was not statistically significant (p = 1.000,

Early infant feeding:

Fisher Exact test).

Ever breastfed

11

(84.6)

1

(25.0)

1.18

0.73 – 6.10

Never breastfed

2

(15.4)

3

(75.0)

0.85

0.16 – 1.37

Table 2: Distribution

of antibody

to HCV

by gender

in study

Maternal HIV and

n*

= 9

n*

= 3

subjects and controls

HCV

status:

Sex

Study

Controls, n (%)

Anti-HCV +ve

4

(44.4)

1

(33.3)

1.12

0.52 – 0.71

subjects, n

HIV

+ve

8

(88.9)

1

(33.3)

2.67

0.83 – 33.18

(%)

Anti-HCV

Anti-HCV

Anti-HCV

Anti-HCV

* n

is the number of mothers of children with positive anti-

positive,

negative,

positive,

negative,

HCV

available for assay

n =

13

n =

119

n =

4

n =

128

Male

8

(6.1)

73

(55.3)

3

(2.4)

80

(6-.6)

Other Risk factors

Female

5

(3.8)

46

(34.8)

1

(0.8)

48

(36.4)

Total

13

(9.8)

119

(90.2)

4

(3.0)

128

(97.0)

Other potential risk factors evaluated for positive HCV

antibody in both study subjects and controls including

(p

= 1.000, Fisher Exact test)

certain cosmetic, religious and cultural practices, unsafe

injections and exposure to blood or blood products as

shown in table 4.

Table 4 depicts the cosmetic, religious or cultural prac-

37

tices that may be potential risk factors for HCV infec-

ences may reflect differences in methods of HCV anti-

tion in children found to be anti-HCV positive among

body assay used and the differences in risk factors de-

study subjects and control groups.

pending on the age variations of populations stud-

ied.****

Of

the 13 study subjects with positive HCV antibody, 8

had tribal marks as against 2 out of 4 controls with posi-

It

was observed in this study that HCV antibody positiv-

tive HCV antibody. This gives a relative risk of a posi-

ity was more frequent after the age of five years. This

tive anti-HCV in study subjects and controls for tribal

was the case among both the study subjects and the Con-

marks, tattoos, uvulectomy, ear piercing, circumcision

trols, with no statistically significant differences be-

and transfusion and their corresponding 95% confidence

tween study subjects and Controls. There was however a

interval were 1.12 (95% CI = 0.68 – 1.98), 1.07 (95% CI

statistically significant difference between rates of HCV

=

0.45 – 1.47), 1.22 (95% CI = 0.63 – 1.64), 0.89, (95%

antibodies positivity and age less than or five years and

CI

= 0.52 – 2.55), 1.39 (95% CI = 0.62 – 2.41) and1.15

beyond. The increased rate of HCV sero-positivity be-

(95% CI = 0.55 – 1.55) respectively. All these were

yond five years found in this study may suggest the rela-

found not to be statistically significant as shown in table

tive importance of post-partum transmission due to

IV. However, 12 of 13 study subjects with positive HCV

greater cumulative opportunities for contact via continu-

antibody had received injections at patent medicine

ous or repeated exposure to risk factors as the child

stores as against a child among the control group. This

grows compared to peri-natal transmission. This is con-

was statistically significant, (RR = 3.69; 95% CI =1.03 -

trary to findings reported among children across eleven

44.55).

tertiary care centres in Nigeria where the median age

was 3.4 years, and elsewhere in which age was found

17

Table 4: Risk

factors for

positive HCV

antibody among

study

not to be significantly associated with anti-HCV sero-

subjects and controls

positivity.

16

The reasons for these differences however

Anti-HCV positive

are unclear. More epidemiologic data on HCV infection

Study

Con-

Rela-

Potential risk

in

HIV-infected children are required to make compari-

subjects,

trols,

tive risk

95%

Confi-

factors

son on the role of age as an independent risk factor. Sex

n =

13

n =

4

dence interval

was

not noted in this study to be of any significance in

Cosmetic, religious/cultural practices:

influencing the rates of HIV/HCV co-infection or HCV

Tribal marks

8

2

1.12

0.68 – 1.98

infection alone. Again this has been previously noted in

Tattoos

4

1

1.07

0.45 – 1.47

adult population. This is contrary to the report from

23

Uvulectomy

Ω

6

1

1.22

0.63 – 1.64

Tanzania

16

Ear

piercing

+

4

2

0.89

0.52 – 2.55

among HIV-infected children in which the

Circumcision

*

5

2

1.39

0.62 – 2.41

prevalence of HCV antibody positivity was significantly

Use of blood/blood products:

higher among girls than boys. On the other hand, the

Transfusion

5

1

1.15

0.55 – 1.55

study across 11 care centres in Nigeria found 76% of

HCV co-infected children to be males. The reason for

17

Unsafe use of sharps:

Injection at

12

1

3.69

1.03 – 44.55

these differences is not clear.

PMV

One aim of this study was to document risk factors of

+

Ear piercing was seen only in girls * Circumcision was seen only

among boys

transmission. The various potential risk factors of trans-

PMV

= Patent medicine vendor

Ω

A

cultural practice done by tradi

mission of HCV in both HIV infected subjects and con-

tional barber

trols were therefore also explored. The possible role of

mode of delivery as a risk factor was examined. Obser-

vations in this study showed that children who were

Discussion

vaginally delivery were 1.6 times more likely to have

positive HCV antibodies than children delivered via

This study has shown the presence of HCV antibodies in

caesarean section. This however was not statistically

HIV infected children aged 2 to 15 years as well as in

significant. There is a similar report of no statistically

age and sex-matched controls. The prevalence of HCV

significant difference between different modes of deliv-

ery and rates of HCV transmission or infection. The

15

antibodies in HIV infected children aged 2 to 15 years

was 9.8%. The prevalence of HCV antibodies in HIV

present study was not able to further segregate delivery

negative children aged 2 to 15 years was 3%. This dif-

methods into normal vaginal or instrumental and as-

ference in the prevalence rates between the study sub-

sisted vaginal deliveries on one hand, and elective or

jects and controls is statistically significant, and suggests

emergency caesarean section on the other hand because

an

increased rate of HCV sero-positivity among HIV

of

inconclusive information from caregivers as to what

infected children. This has been previously documented

type of vaginal delivery or section was used in some

by

other workers in Tanzania

16

and

also across Africa

cases. There is nevertheless a case of a clinically in-

among different adult populations.

20-24

The 9.8% HIV/

creased risk of HCV antibody positivity when delivered

HCV co-infection rate found in this study is far lower

via vaginal route over caesarean section.

than the 20.2% rate reported in Jos among adult popula-

tion, but much higher than rates of 0.02% - 3.3% re-

25

Breastfeeding was another potential risk factor explored

ported by other workers in paediatric population

17

and

in

this study. It was observed that breastfed children in

elsewhere among adult populations.

26-27

These differ-

the study were 1.18 times as likely to have a positive

38

HCV antibody as their non-breastfed peers. Again, this

study. Five of the 13 children (38.5%) among the study

was not of statistical significance. The marginal increase

subjects with a positive HCV antibody had a history of

in

risk was in keeping with other studies that showed

previous blood transfusion as against one of four (25%)

that transmission via breast milk was not a significant

among the controls with positive HCV antibodies. This

mode of transmission in spite of detection of HCV RNA

was not a statistically significant difference. The finding

in

the breast milk of viraemic mothers.

15,

20

It

was sug-

in

this study was not entirely unexpected as transfusion

gested that acquisition of HCV by children through

of

blood or blood products carried out in standard health

breastfeeding will be dependent on the viral load in the

facilities offering transfusion services such as this centre

breast milk, which is usually said to be highest soon

usually screen the blood or blood component for HCV.

after delivery. It was not possible to substantiate this in

28

Significant HCV nosocomial transmission through

the present study because maternal HCV viral load in

transfusion of blood or its components would only occur

blood or breast milk was not determined.

in

settings with absence of blood screening services.

That was not the setting in this environment.

This study however determined the maternal HCV anti-

Certain cosmetic, cultural or religious practices were

body status and how it relates to HCV antibody positiv-

identified in the present study to marginally raise the

ity

in both the study subjects and the controls. It was

risk

of positive HCV antibodies. These included tribal

noted that HCV seropositive mothers with HIV infection

marks and tattoos, which increased the chances of trans-

had

a 12% increased chance of having children with

mission by 1.12 and 1.07 times more than in those with-

HCV antibody positivity than HCV sero-negative moth-

out these procedures respectively. These figures how-

ers. Although a mother with HCV infection could trans-

ever did not reach statistical significance. Other risky

mit it vertically to her children, this however does not

practices of note in this study were uvulectomy and cir-

conclusively prove route of transmission.

cumcision, which increased the probability of HCV anti-

body positivity by 1.22 and 1.39 times respectively more

This study was not designed to determine the route of

than in children who did not have them. Again, these

HCV transmission for co-infected children. Further tests

were not statistically significant.

would be required to confirm if transmission was mother

-to- child when mother-child pair is found to have HCV

All these practices, especially tribal marks, tattoos and

infection, since both may have acquired the HCV infec-

uvulectomy, and to a less extent circumcision, in our

tion from the same source. It was not possible from the

environment are carried out by traditional barbers, often

design of the present study therefore to speculate on

using the same blade for multiple subjects with little or

possible vertical transmission of HCV infection among

no

sterilization before re-use. This setting would highly

favour HCV transmission.

10

study subjects and controls.

This study has demon-

strated weak associations of these very common prac-

Maternal HIV infection was observed to enhance HCV

tices in our environment with HCV antibody positivity,

antibody positivity in children in this study. Eighty eight

which because of their widespread practice in the com-

percent (8/9) of mothers of children with positive HCV

munity cannot be overlooked as potentially risky proce-

antibodies available for assay were HIV infected among

dures.

the cases as against one of three (33.3%) corresponding

mothers among the controls. Children whose mothers

Surprisingly, it is noteworthy that this study found no

were HIV infected were found to be more than twice as

association between ear piercing and HCV antibody

likely to have HCV antibody positivity as children

positivity. It was expected that this very common cos-

whose mothers were HIV negative. This is in confor-

metic and cultural practice in the community would also

mity with reports that vertical transmission rates for

be

potentially risky considering that non-professionals

HCV were 8 to 40% higher for women who were also

commonly perform it. In this study however, it was ob-

HIV infected.

15

served that children who had their ear pierced had 0.89

times the probability of HCV antibody positivity than

The role of some other potential risk factors for trans-

girls who did not have ear piercing done. Perhaps a

mission was also explored. Results from this study sug-

plausible reason for this relative decreased risk may be

gested that unsafe therapeutic injection practice by pat-

because of the less likelihood of re-use of needle used

ent medicine vendors was a very significant risk factor

for the procedure than in other cultural procedures such

for HCV transmission in this environment. Twelve of

as

circumcision or uvulectomy.

thirteen (92.3%) children with positive HCV antibodies

Overall, this study has demonstrated the prevalence of

among the study subjects were noted to have had a his-

HCV antibody in HIV infected children to be statisti-

tory of injection at patent medicine shops as against a

cally different from that in HIV negative children. This

quarter of children with positive HCV antibodies among

underscores the importance of routine screening of all

the controls. This was a statistically significant differ-

HIV-infected children for HCV infection, to avail them

ence between the groups. This was much higher than the

with prompt and adequate treatment. The study has also

39% of co-infected patients reported in one cohort of

documented some possible risk factors for HCV/HIV co

having had a history of needle injection at patent medi-

-infection in these children and highlights the need to

cine stores.

23

provide safer injection practices especially to HIV in-

Blood transfusion was yet another risk factor usually

fected children through a combination of education, leg-

associated with HCV infection explored in the present

islation and regulation of patent medicine vendors.

39

Conflict of interest: None

Funding: None

References

1.

Rockstroh JK and Spengler U.

10.

WHO. Hepatitis C - global preva-

20.

Muktar HM, Alkali CN, Jones EM.

HIV

and hepatitis C virus co-

lence (update) Wkly Epidemiol

Hepatitis B and C co-infections in

infection. Lancet

Infect Dis

2004;

Rec.1999;74:425-7.

HIV/AIDS patients attending ARV

4: 437-44

11.

Nigeria Federal Ministry of

center ABUTH, Zaria, Nigeria.

2.

Bica I, Mcgovern B, Dhar R,

Health. Technical Report on 2005

HMR J 2006;4:39-45.

Stone D, McGowan K, Scheib R et

National HIV/Syphilis Sentinel

21.

Ayele W, Nokes DJ, Abebe A,

al. Increasing

mortality due

to end

Survey among pregnant women

Messele T, Dejene A, Enquselassie

-stage liver disease in patients with

attending antenatal clinics in Nige-

F

et al. Higher prevalence of anti-

human immunodeficiency virus

ria. Abuja. Nigeria: FMOH;2005.

HCV

antibodies among HIV-

infection. Clin.

Infect. Dis.

2001;

12.

Madhava V, Burgess C, Drucker

positive compared to HIV-negative

32:492 – 7

E.

Epidemiology of chronic hepati-

inhabitants of Addis Ababa,

3.

Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Di

tis

C virus infection in sub-Saharan

Ethiopia. J

Med Virol2002;68:12-7

Martino V, Charlotte F, Azira F,

Africa. Lancet

Infect Dis

2002;2:

22.

Agwale SM, Tanimoto L, Womack

Coutellier A et al. Liver fibrosis

293-302.

C,

Odama L, Leung K, Duey D et

progression in human immunode-

13.

Mboto CI, Davies A, Fielder M,

al.

Prevalence of HCV co-infection

ficiency virus and hepatitis C virus

Jewell AP. Human

in

HIV-infected individuals in

coinfected patients. The Multiviric

immunodeficiency virus and

Nigeria and characterization of

Group. Hepatology

1999;30:1054

hepatitis C co-infection in sub-

HCV

genotypes. J

Clin Virol

–

1058.

Saharan West Africa. Br

J Biomed

2004;31:S3-6.

4.

Sulkowski MS, Mast EE, Seeff

Sci. 2006;63:29-37.

23.

Inyama PU, Uneke CJ, Anyanwu

LB,

Thomas DL. Hepatitis C Vi-

14.

Koziel MJ, Peters MG.Viral Hepa-

GI,

Njoku OM, Idoko JH, Idoko

rus

Infection as an Opportunistic

titis in HIV Infection. N

Engl J

JA.

Prevalence of antibodies to

Disease in Persons Infected with

Med 2007:356;1445-54.

Hepatitis C virus among Nigerian

Human Immunodeficiency Virus.

15.

Nigro G, D’Orio F, Catania S,

patients with HIV infection.

Online

Clin Infect Dis 2000;30:S77-84

Badolato MC, Livadiotti S, Ber-

J Health Allied Scs.2005;2:2

5.

Greub G, Ledergerber B, Battegay

nadi S et al. Mother to infant trans-

24.

Forbi JC, Gabadi S, Alabi R, Ipere-

M,

Grob P, Perrin L, Furrer H, et

mission of coinfection by human

polu HO, Pam CR, Entonu PE,

al.Clinical progression, survival,

immunodeficiency virus and hepa-

Agwale SM. The role of triple

and

immune recovery during anti-

titis C virus: prevalence and clini-

infection with hepatitis B virus,

retroviral therapyin patients with

cal

manifestations. Arch

Virol

hepatitis C virus, and human im-

HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus co-

1997;142:453-457.

munodeficiency virus (HIV) type-1

infection: the Swiss HIV Co-

16.

Telatela SP, Matee MI, Munubhi

on

CD4 + lymphocyte levels in the

hortStudy. Lancet.

2000;356:1800

EK.

Seroprevalence of hepatitis B

highly HIV infected population of

-5.

and

C viral co-infections among

North-Central Nigeria. Mem

Inst

6.

Sulkowski M, Thomas D, Mehta

children infected with human im-

Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:535-537.

S,

Chaisson R, Moore R. Hepato-

munodeficiency virus attending the

25.

Gwamzi N, Hawkins C, Meloni S,

toxicity associated with nevirapine

paediatric HIV care and treatment

Muazu M, Badung B, et al. Impact

or

efavirenz-containing antiretro-

center at Muhimbili National Hos-

of

Hepatitis C Virus on HIV-

viral therapy: role of hepatitis C

pital in Dar-es-Salam, Tanzania.

infected individuals in Nigeria.

and

B infections. Hepatology

BMC

Public Health 2007;7;338.

Abstact 921. 14th Conference on

2002;35:182-189.

17.

Rawizza H, Ochigbo S, Chang C,

Retroviruses and Opportunistic

7.

Tossing G. Management of

Melonil M, Oguche S, Osinusil K,

Infections Los Angeles, California,

chronic hepatitis C in HIV-

etal . Prevalence

of Hepatitis

Co-

February 2007.

coinfected patients – results from

infection Among HIV-Infected

26.

Ejele E, Osaro E, Chijioke AN.

the

First International Workshop

Nigerian Children in the Harvard

The

Prevalence of Hepatitis C

on

HIV and Hepatitis Co-

PEPFAR ART Program. Confer-

Antibodies in Patients With HIV

Infection, December 2-4, 2004,

ence on Retroviruses and Oppor-

Infection In The Niger Delta Of

tunistic Infections; February 16 -

th

Amsterdam, Netherlands. Eur

J

Nigeria Osekhuemen. Highland

19

; San Francisco CA; 2010.

th

Med Res 2005;10:43-5.

Med Res J. 2005;3:11-17.

8.

Gisselquist D, Perrin L, Minkin

18.

Resti M, Azzari C, Bortolotti F.

27.

Inyama PU, Uneke CJ, Anyanwu

SF.

Parallel and overlapping HIV

Hepatitis C virus infection in chil-

GI,

Njoku OM, Idoko JH, Idoko

and

bloodborne hepatitis epidem-

dren coinfected with HIV: epide-

JA.

Prevalence of antibodies to

ics

in Africa. Int

J STD

AIDS

miology and management. Pediatr

Hepatitis C virus among Nigerian

2004;15:145 – 152.

Drugs 2002;4:571-80.

patients with HIV infection.

Online

9.

UNAIDS/WHO The Joint United

19.

Schuval S, Van Dyke RB, Lindsey

J Health Allied Scs.2005;2:2

Nations Programme on HIV/

JC,

Palumbo P, Mofenson LM,

28.

Rousseau CM, Nduati RW,

AIDS/World Health Organization.

Oleske JM et al. Hepatitis C Preva-

Richardson BA, Steele MS, John-

AIDS epidemic update. UNAIDS/

lence in Children with Perinatal

Stewart GC, Mboi-Ngacha DA et

WHO. [Internet]. 2006. [cited

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

al.

Longitudinal analysis of human

2007 Sep 3]. Available from:

Infection Enrolled in a long-term

immunodeficiency virus type 1

http://www.who.int/hiv/

Follow-up Protocol. Arch

Pediatr

RNA

in breast milk and its

mediacen-

Adolesc Med2004;158:1007-1013 .

relationship to infant infection and

tre/2006_EpiUpdate_en.pdf

maternal disease. J

Infect Dis

2003;187:741-47.